The relationship between climate change and human health is complex, requiring advanced modeling to evaluate its effects.

Climate drivers such as extreme temperatures, air pollution, and natural disasters interact with socioeconomic factors, influencing mortality and morbidity rates. Actuaries and insurers must consider data gaps and methodological inconsistencies when assessing these risks and their implications for pricing assumptions.

Dr. Georgiana Willwerth-Pascutiu, vice president and medical director of Global Medical at RGA International Re, has examined these issues in depth, emphasizing the need for a comprehensive approach to understanding the health impacts of climate change.

Read next: Addressing the emerging risks of 2024

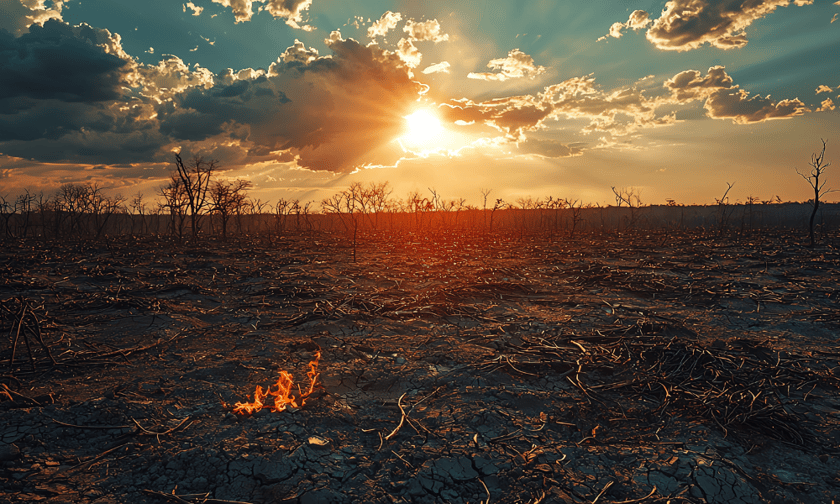

Among the most studied climate drivers are air pollution and rising temperatures, which include extreme heat events. However, floods and droughts have had the most significant global human toll.

According to the Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change, flood-related mortality has remained stable since the 1990s, with declines in some high-income countries.

Over the past two decades, cold-related excess mortality has declined globally by 0.5%, while heat-related excess mortality has increased by 0.2%, leading to a net reduction.

Southeast Asia recorded the largest decline. Future projections suggest that under a high-emission scenario, temperature-related mortality will remain neutral in the US but could increase in Southeast Asia.

“Our task is to understand the epidemiological relationship between climate hazards and health, how it varies by geography and other socioeconomic factors, and then to quantify the impact of climate change on health,” said Willwerth-Pascutiu.

The Global Burden of Disease study attributed 1.9 million deaths in 2021 to non-optimal temperatures, with cold-related mortality approximately nine times higher than heat-related mortality. However, estimates range from 1.7 million to 5 million deaths, reflecting inconsistencies in data collection.

Official records may underreport climate-related deaths. An Australian study suggests heat-related mortality could be underestimated by a factor of 50. Improved use of International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes could enhance reporting accuracy.

Attribution science examines how climate change influences extreme weather. Rising ocean temperatures have been linked to stronger storms, with some projections estimating a 10%-15% increase in storm frequency by 2050.

A Nature study estimates nearly 100,000 annual deaths from PM 2.5 exposure due to wildfires, with 13% attributed to climate change.

Willwerth-Pascutiu underscored the need for improved data collection and broader assessments.

How should insurers and policymakers respond? Share your thoughts in the comments.