Cyber risks continue to throw major challenges at insurers and brokers. Aon’s recent Cyber Insurance Market Insights report referred to cyber as “the most distressed line of insurance” with premiums rising more than 100%. The State of Cyber Resilience, by Marsh and Microsoft, found that many companies worldwide are anything but cyber resilient with 75% of them victims of at least one cyberattack.

In response to these challenges, last month, Lloyd’s of London announced a cyber mandate that will force its managing agents to exclude state-backed cyberattacks and war from standalone cyber policies.

Insurance Business reached out to cyber experts for their response. Ismael Valenzuela, vice president of Threat Research and Intelligence at BlackBerry was sceptical about the practicality of such a mandate.

“From my perspective, as a cybersecurity expert, we can never attribute something 100% to a specific actor because what we have is digital evidence and digital evidence can be manipulated in many different ways,” said the New Jersey based cyber expert.

Read more: How practical is Lloyd’s cyber mandate?

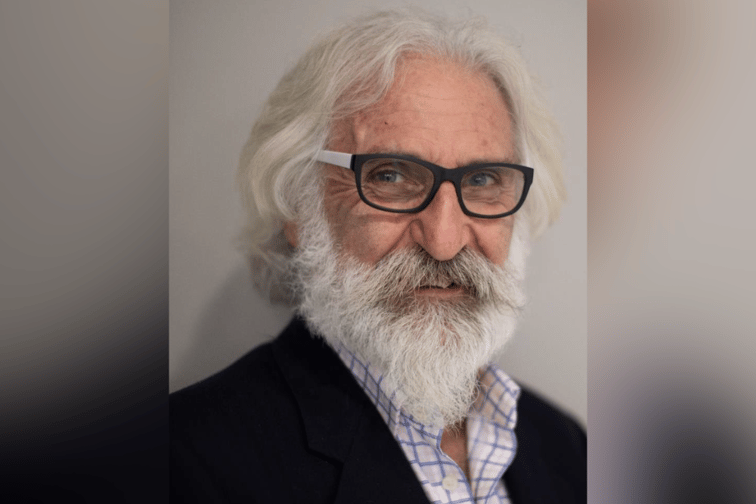

“The exclusion is not unexpected,” said Colin Pausey (pictured above), chief operating officer for Emergence Insurance, based in Sydney. “Lloyd’s objective is to be proactive to ensure the sustainability of the cyber insurance market, of which it is a leader.”

Emergence is a cyber insurance specialist underwriting agency.

Read next: What is an underwriting agency?

“Other cyber insurers will likely follow the Lloyd’s lead,” said Pausey who wasn’t aware of any similar exclusions but said discussions around excluding state-based threat actors is not new.

“War is generally excluded from insurance,” he said. “Lloyd’s is looking at a state-based cyber threat as a form of modern war – but specifically excluding it and not relying on tinkering with the war exclusion.”

Pausey agreed with Valenzuela and said attribution of these types of cyberattacks is always a challenge, but he said the exclusion will most likely be applied only where attribution is clear.

“For example, in 2017/2018, the UK, USA and Australia attributed the NotPetya attack to Russia,” he said. “The exclusion can apply if there is attribution by the government in which the state-based act occurs - and these acts often ignore conventional borders.”

Pausey said where there is no attribution, the onus is on the insurer, on the balance of probabilities, to prove attribution, based on what information is available.

“The onus is always on the insurer to establish an exclusion,” he said.

Pausey said in cases like the NotPetya attack, the Lloyd’s exclusion should be able to be satisfied.

“If there is no attribution by the state in which the state-based attack occurs - which is the attack that gives rise to the claim under the cyber policy - but there is attribution by ally states, such as attribution by some members of the 14 Eyes Agreement, for example, that may be sufficient for Lloyd’s to establish attribution,” he said.

However, Pausey said, if it’s not attributed by a government, proving attribution for these types of cyberattacks will be difficult.

“Governments have the benefit of access to intelligence information that insurers don’t, so with no government attribution, that will limit when an insurer can rely on the exclusion,” he said.

Despite the ongoing reports from insurers and brokers highlighting the sharply rising premiums and cyber market challenges, Pausey did not agree that the Lloyd’s cyber mandate is another indication of the industry’s struggle with cyber risks.

“I don’t agree that the insurance industry struggles with cyber risk,” he said. “Cyber is not a static risk.”

He said the mandate is about managing potential cyber risk exposure and potential systemic cyber losses.

“The market can only cover what is affordable and commensurate with premiums,” said Pausey. “State-based attacks are seen by Lloyd’s as a challenge to the sustainability of cyber insurance and they are being proactive in attempting to manage the risk through the proposed exclusion.”

The Emergence COO sees the mandate as a further sign that cyber insurance policies are evolving to meet the changing cyber threat landscape.

Last month, Pausey’s agency warned that Australia’s regulators are taking cyberattacks seriously enough to start prosecuting companies that fail to implement adequate measures to stop them.

“There will be more prosecutions, particularly by the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC), regardless of whether an organisation is a victim of crime like a ransomware attack,” said Pausey to IB last month.

Pausey said a recent, Australia-first court case is the start of more prosecutions against companies, including insurers.

In May, the Federal Court found that RI Advice breached its AFS license obligations by failing to have adequate risk management systems to manage its cybersecurity risks.

In one incident the court said a “malicious agent” obtained unauthorised access to a file server for nearly six months before being detected by the firm. The breach resulted in the possible compromise of the sensitive and personal information of several thousand clients and other persons.

RI Advice was ordered to pay $750,000 towards the Australian Securities and Investments Commission’s (ASIC) costs and take adequate cyber security measures.