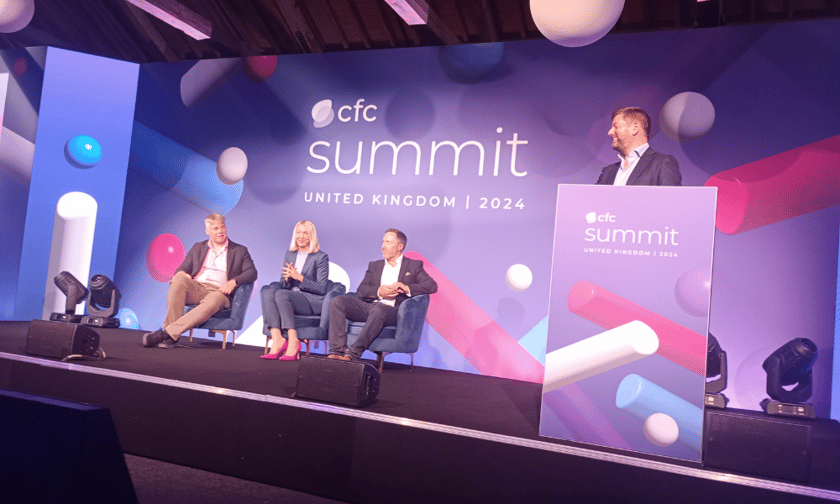

At the 2024 CFC Summit, CEO Andy Holmes (pictured centre, right), threw down the gauntlet to the insurance industry, noting that while insurance is built on trust, “a lot of the claims experience that is delivered breaches that trust”.

In his address, Holmes – who started his three-decade career in a claims role – addressed some of the key points in the insurance distribution chain where the claims experience breaks down. Too many times the first communication from the insurer to the customer at the point of claim is a reservation of rights letter, he said, which the customer reads and thinks of as the insurer trying to wriggle out of their obligation to pay the claim.

“Then there’s the delays,” he said. “Delays in communicating progress on the claims, lots of radio silence increasing customer agitation, delays in paying the claim. We can wire money in seconds, [why] does it take weeks or months to move claims monies? This really substandard customer experience too often gives our industry the reputation of being a bunch of scammers who are happy to take the customer’s premium but are nowhere to be seen when it comes to claims time.”

While the vast majority of insurance claims experiences are better than that, the good experiences don’t make the headlines and so the public perception of insurance is inherently negative. But it doesn’t have to be this way, according to Holmes. The technology revolution of the last 30 years has led to the first digital-native insurance generation. This generation has a unique opportunity to change not just the public perception of insurance and the reputation of what it means to work in the industry, but also the fundamentals of the insurance proposition.

Digging into what this reimaging of insurance might look like, Holmes pointed to the proposal forms issued to clients as a primary example. CFC’s cyber insurance proposition means it can now quote cyber coverage from just the company’s web address, but crucially, also that it can identify how vulnerable a client or prospective client is against cyber threats, whether they’ve been compromised or not. This isn’t information just to be used to select or price customers more effectively, he said, it’s a critical tool to moving the dial from insurance from a ‘promise to pay’ to a ‘promise to protect’.

Better data and information on a customer also mean the industry can shift away from a siloed approach to protecting businesses and move to a joined-up solution. “Insurance is the least interesting thing our customers do all year, as far as they’re concerned,” he said. “So, let's sell them all the relevant covers for their business in a one-stop-shop and let them move on.”

Beyond that onboarding process, the next opportunity is within the policy lifecycle experience, Holmes said. The better insurers nowadays are looking after their clients throughout that entire lifecycle, spotting vulnerabilities and delivering time-critical threat alerts. It’s about moving the conversation around insurance from an annual touchpoint to an ongoing service offering.

"If we take things one step further, what happens if we remove exclusions from our policies?” Holmes posited. “Exclusions we all come to know and love, but the public sees them as weaselly worded, small print that gives us an excuse to wriggle off claims… Having fewer or no exclusions would certainly rebuild trust with the public that insurers will actually be there for them at that critical moment.”

Digging into his reasoning behind that, Holmes invited the Summit audience to think about the reality of the data. Taking professional liability for example, he said, when you look at the exclusions around that product line, there are only really two used with any frequency – a circumstance known as inception exclusion and a retroactive data exclusion. “The rest are just window dressing. Comfort blankets for insurers and signs of threats for customers.”

“Both those exclusions can be built in to the scope of cover as defined by the insuring clause,” he said. “Then, think also, of all the money we spend as insurers fighting our customers over coverage. Not only does it cost a lot of money in pound-notes terms, but it erodes goodwill and trust massively. My view is that we spend way more each year on coverage counsel and other advisors to fight claims than we would do in paying the additional claims we’d have because we had fewer or no exclusions.”

Having spent 21 years at CFC actively involved in writing the words that form its policy documents, he noted that there are certain exclusions which the firm is required to have by the regulator, as a regulated business. But beyond those exclusions, he said, his time in the market has shown that there’s little point in having an exclusion which is not exercised. “It just erodes trust. It elongates the policy form and our policy forms are way longer, way more complex, [containing] way more legalese than they ever should be. And it makes the product inaccessible.”

Also critical to bear in mind, Holmes said, is that as a percentage of GDP, customers are now spending less on insurance now than they were 20 years ago. The industry is fast becoming less relevant at a time when the external risk environment dictates that it should be and is more relevant than ever. He believes that part of the reason for that is the lack of trust people have in insurance, which is why he’s inviting the market to reimagine insurance and its relevance.

Invited to offer a counter perspective, Dan Trueman (pictured left), who joined CFC as CUO earlier this year, said that overall, he agrees with Holmes’ perspective. There are some fundamental exclusions that shape the policy, he said, but many of those could be put in the insuring clause because the problem that the wider industry faces is how to make sure its policies are easy to read and understand, and simple for brokers to communicate to clients. “I would suggest that at least 50% of our exclusions [do not] need to be there. And I think we should hold ourselves to trying to get rid of them.”