Markets are soaring. The economy is doing fine. And yet, 2018 doesn’t feel good.

Despite entering the new year with a positive financial outlook, we could see one wrong move ignite geopolitical chaos. “The global order is unravelling,” says Eurasia Group president Ian Bremmer and chairman Cliff Kupchan. This year’s Top Risks report from his organisation doesn’t sugar-coat any of its projections. “If we had to pick one year for a big unexpected crisis—the geopolitical equivalent of the 2008 financial meltdown—it feels like 2018,” say Bremmer and Kupchan. “Sorry.”

On course for a geopolitical depression, the world order is fracturing from blows to the legitimacy of liberal democracies, declining US influence and the consequent vacuum, a rise in protectionism, and competition for tech dominance. Without a hegemon to establish a new order, the geopolitical environment presents a much greater risk than the markets currently suggest. “You have this unusual situation where risks are really elevated and exceptionally dangerous, yet the economy continues chugging along,” says Bremmer.

Here are Eurasia’s highlighted top-ten risks to look out for in 2018:

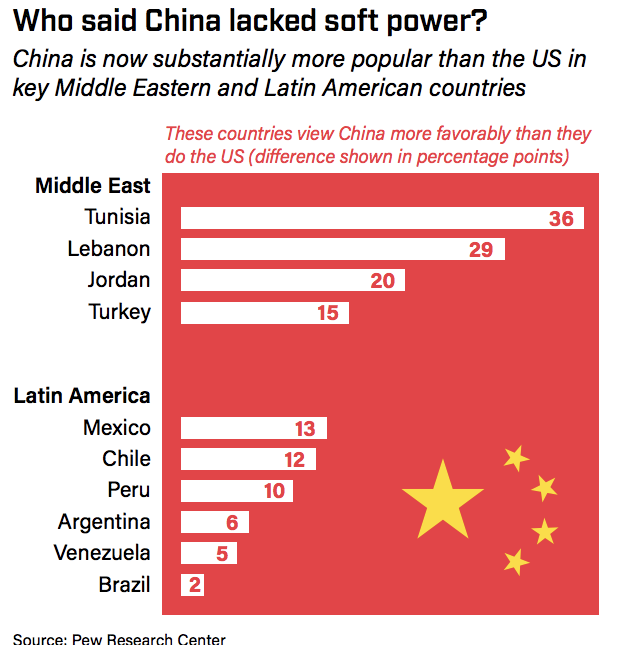

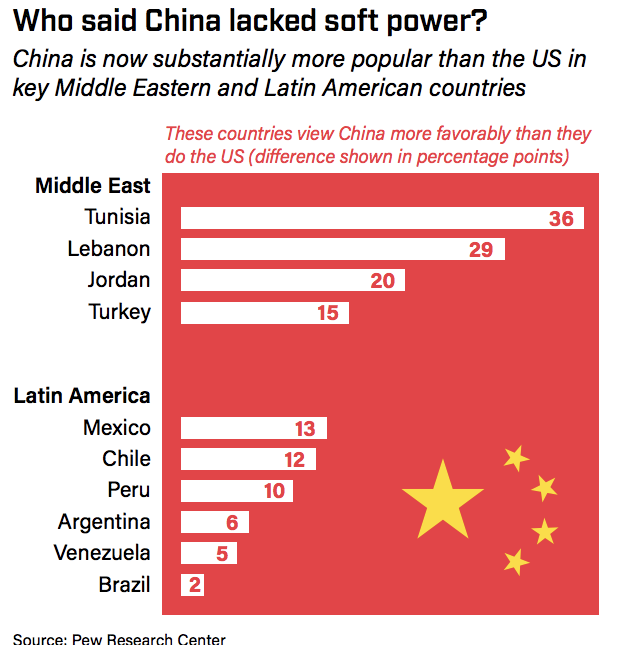

- China loves a vacuum

China is coming to power at the same moment that the US experiences its weakest leadership in modern history. In a shifting world order, the protectionist retreat highlighted by Trump’s “America First” mantra has created a power vacuum just when President Xi Jinping’s China finds itself in the strongest geopolitical position of any Chinese leader since Mao. This creates several almost unprecedented risks:

- The global business environment will have to adjust to entirely new standards, which will raise the cost of doing business

- Asian geopolitics will be polarised between the US and China’s regional allies

- Xi’s increasing control could pose a threat to China’s long-term economic trajectory

- Accidents

This risk is all about the potential for mistakes. Cyberattacks, war with North Korea, terrorist attacks, US-Russia relations, and the war in Syria all have the potential to drive a wedge into geopolitical stability. It’s impossible to predict that an ‘accident’ will happen, but with geopolitical risks continuing to proliferate, the odds that missteps can be avoided become ever weaker.

.jpg) click to enlarge

click to enlarge

3. Global tech war

The vast economic potential brought by emerging technologies will instigate 2018’s biggest power struggle, particularly with the emergence of next-generation technologies like AI and super-computing. “That revolution is happening in two countries: The US and China,” says Bremmer. “This is a fight between two very different models, and increasingly a fight that either one could win.” For now, the US still has the best talent, but China is pouring resources into closing the lead. They’ll also continue to struggle for market dominance as both compete to be the top technology supplier in areas of civilian infrastructure, consumer goods, and government procurement and security equipment. Decreased potential for cooperation between the two countries in other arenas compounds the risk.

.jpg) click to enlarge

click to enlarge

4. Mexico

2018 will be a big year for Mexico, and much could go wrong. “The idea that Mexico is risk number four — if you had said that five years ago, you would have thought that was insane,” says Bremmer. “And yet the stars have all aligned against Mexico in 2018.” The first big hurdle is the renegotiation of NAFTA. Success of the deal lies very much in question, but an impasse would spur economic uncertainty. Mexico would bear the brunt of it. At the same time, the presidential election favours Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, who offers a fundamental break from the current government, which voters increasingly distrust.

.jpg) click to enlarge

click to enlarge

5. US-Iran relations

Trump has big plans for Iran: minimising Iran’s regional influence through stronger support for Saudi Arabia; increased sanctions; and as seen recently, public support for anti-government protesters. Tensions across the region will be exacerbated by a retaliatory Iran, which will spell trouble for investors. Eurasia group cautiously projects that the nuclear deal will last through the year. “It’s a hell of a close call,” says Kupchan. If it doesn’t, it’s likely that Iran would grow its nuclear program, which would increase the threat of US or Israeli strikes on the country and consequently boost oil prices.

.jpg) click to enlarge

click to enlarge

6. The erosion of institutions

Growing distrust of the legitimacy of institutions will be an important global narrative in the coming year. Eroded faith in electoral processes, suspicion of the media, and the advent of “fake news” across the developed world will continue to stoke anti-establishment sentiments. Brexit and Trump’s election are clear examples, but the trend has reached developing countries, too. Erosion of political institutions poses a threat to structural stability in the global system and will increase the potential for conflict.

.jpg) click to enlarge

click to enlarge

7. Protectionism 2.0

Growing anti-establishment sentiments are pressuring policymakers to adopt more mercantilist approaches to global economic competition. With growing Chinese assertiveness and without US leadership to direct a new order, governments are putting up barriers. Moving beyond the traditional sectors like agriculture and manufacturing, the new barriers are also in the digital economy and innovation-intensive industries. They’re less transparent, too. New measures like bailouts and subsidies are replacing import tariffs and quotas. As always, politics has a role to play, too. The new measures are often politically motivated, at least on a micro level. The resulting resentments could be damaging geopolitically.

.jpg) click to enlarge

click to enlarge

8. United Kingdom

Brexit woes won’t go away for the UK anytime soon. Fighting over details of the negotiations will continue seemingly endlessly. If Prime Minister Theresa May loses her job in the process, she’ll likely be replaced by a Tory hardliner, but if Jeremy Corbyn pulls a surprise and wins a new election, both Article 50 talks and domestic economic policy will suffer.

.jpg) click to enlarge

click to enlarge

9. Identity politics in southern Asia

The identity politics prominent in the US and Europe has infected southern Asia, too. The strains present in Southeast Asia and the Indian sub-continent are primarily Islamism, anti-Chinese and other minorities, and growing Indian nationalism. In Indonesia and Malaysia especially, the majority Muslim population is emboldened by fears of perceived injustice. Across the region, resentment is once again rising against ethnic Chinese in response to their often-disproportionate share of wealth. In India, there’s fear that Prime Minister Narenda Modi will stoke Hindu nationalism ahead of 2019 elections and provide a cover for radicalised factions of society.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)