Hurricane Otis, the Category 5 storm that devastated Acapulco last year, is likely to hold more lessons for catastrophe modelers and insurers than any other major storm since Hurricane Andrew more than three decades ago, analysts at Moody’s RMS have said.

Otis made landfall on Mexico’s southern Pacific coast with sustained winds of 165mph last October after a rapid intensification that saw the storm’s wind speeds increase by 115mph in less than 24 hours, leaving more than a million people in Acapulco scrambling to prepare.

The major storm, which was the first category 5 hurricane on record to make landfall on Mexico’s West coast, drove catastrophic damage.

High-rises took a pummeling and more than 80% of the city’s hotels were damaged by the storm, according to reports citing comment from Governor of Guerrero Evelyn Sagaldo. Power was knocked out and a power plant damaged, while mudslides that followed the storm added to the devastation.

Insured losses from Hurricane Otis have been estimated at between $2.5 billion and $4.5 billion by Moody’s RMS.

Economic losses from the storm are expected to total $15 billion, according to Aon, making the major hurricane one of the costliest events in Mexico’s history.

The storm’s rapid intensification “underscores… the notion that history isn’t a great predictor for what might happen going forward,” James Cosgrove, Moody’s RMS senior modeler, said during a media briefing call on Tuesday.

With much left to “digest” given the relatively recent storm impact, Otis having made landfall on August 25, 2023, Moody’s RMS has been evaluating its models for the Pacific portion of Mexico.

“[Given the] category 5 landfall in a very densely populated area, a modern city with modern high rises, I don’t think we’ve ever seen that kind of an opportunity to learn and to gather so much useful information, probably since Hurricane Andrew in 1992,” said Jeff Waters, Moody’s RMS staff product manager, model management. “This is going to give us a lot of opportunity to learn and to grow and to help innovate our CAT models in addition to educating the broader market in terms of resilience and having an opportunity to build back better.”

Construction quality has proved a key takeaway for modelers thus far, with buildings having been designed to withstand earthquakes but not major hurricanes.

Typically, buildings in Acapulco were built to withstand wind speeds of between 90mph to 120mph, according to Moody’s RMS, and proved little match for Otis’ destructive intensity.

With much take up of insurance in the region concentrated on coastal areas and hotels, there are questions over whether the event could spur demand for cover and act as “catalyst” for closing the protection gap, Waters said.

Similar questions were raised in the aftermath of Andrew, which tore through the Bahamas, Louisiana, and Florida in 1992 and has been credited with driving insurance industry adoption of CAT models.

Like Otis, Andrew underwent a rapid intensification before slamming into Southern Florida, rendering around 250,000 people temporarily homeless, according to NHC figures.

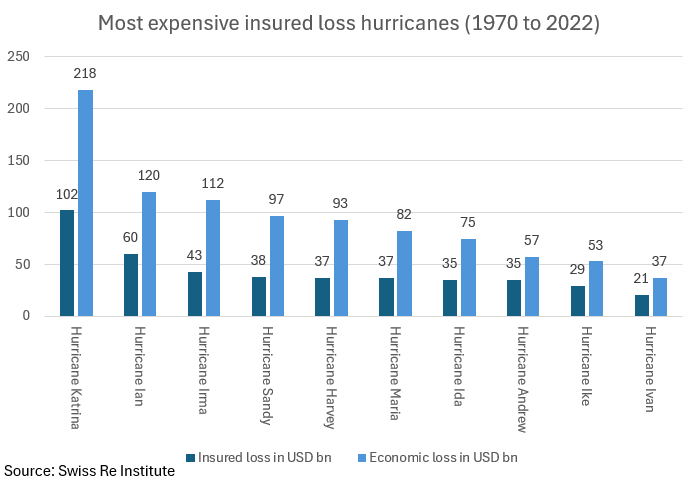

Andrew’s economic cost was more than $26 billion in Florida alone, with the state’s insured losses totaling $15.5 billion, according to figures from Swiss Re.

In the years that followed, Florida enacted new building codes, with the state-wide Florida Building Code (FBC) implemented in 2002 encompassing high-velocity hurricane zones in Miami-Dade and Broward County.

Seven domestic insurance companies and one foreign company entered insolvency due to Andrew’s impact, while others became “technically insolvent” and were propped up by parent company funds transfers, according to an Insurance Information Institute (Triple-I) analysis.

Got a view on catastrophe modeling in the wake of Hurricane Otis? Leave a comment below.