A longtime Florida state lawmaker and leader on insurance policy is questioning the integrity of reinsurance rate-setting while advocating for federal legislation he says would reduce Florida homeowners’ annual premium increases by up to 25% by reining in reinsurance expenses.

A trade association representing the reinsurance sector disputed the assertion that reinsurance is a primary contributor to soaring insurance costs.

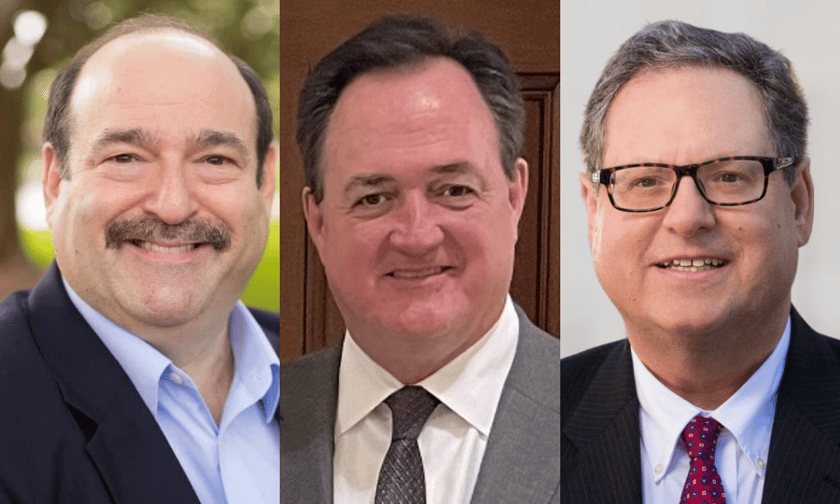

Broward County Commissioner Steve Geller (pictured above, far left) said reinsurance accounts for about half of the cost of homeowners’ insurance, according to a study he presented to a joint meeting of the South Florida and Treasure Coast Regional Planning Councils on March 15.

The analysis supports a bill introduced in Congress last year, the Natural Disaster Risk Reinsurance Program Act, that would make the federal government the reinsurer of last resort to help states cope with hurricanes, wildfires, tornadoes, earthquakes and other natural disasters.

If reinsurance cost pressure is eased through a national program, it would cut annual homeowners’ premium growth by 25% in Florida and by 12.5% nationwide, according to the study. The average Florida homeowner would save $1,500 in the first year, and more later, the study said.

Geller is a skeptic of how reinsurance rates are determined.

“They are not actuarily sound,” Geller said in an interview. “They’re based on whatever the market will bear. If you reduce the cost of reinsurance, that automatically reduces the cost of insurance.”

The Reinsurance Association of America opposes the bill and denied that reinsurance is responsible for pushing up homeowners’ premiums. Instead, those costs are stoked by inflation, the trend toward building in high-risk areas, the proliferation of lawsuits and the increasing frequency and severity of natural disasters, the group said.

“Any increases in reinsurance costs due to the driving cost factors, or any decreases in reinsurance costs, have a di minimis impact on policyholder premiums, and therefore, reinsurance is not the issue,” RAA President Lee Covington (pictured above, middle) said in a statement. “Rather, reinsurance spreads the risk and costs across the globe, versus placing the burden on the American taxpayers.”

The Insurance Information Institute also questioned promises that the legislation would result in homeowners’ insurance savings.

“The modeling that this bill would reduce premiums is not realistic,” Mark Friedlander, director of corporate communications at Triple I (pictured above, right), said in a statement.

Under the bill, the federal government would float bonds to help states pay damages that exceed a certain threshold. Most homeowner policies pay reinsurance rates that would cover a storm that is likely to occur once in more than 100 years, Geller said.

Florida has not been hit by one of those storms since the 1920s, Geller said. Customers would reap insurance savings if reinsurance only covered one-in-50-year weather events.

The national program envisioned in the bill would kick in for the low-probability catastrophic disasters causing non-flood insured residential property damage.

The federal bonds, which would carry Treasury-bill rates, would be paid off over 10 years by a surcharge on homeowners’ premiums that would amount to 1% to 2%, Geller said.

The surcharge incurred to pay for bonds for “very, very, very rare occurrences” would be worth the annual premium savings generated by trimming reinsurance costs, Geller said.

States would be able to opt in to the reinsurance coverage. Geller emphasized the program would not burden the rest of the country with Florida’s insurance bills.

“I’ve figured out how to do it without costing Iowa taxpayers a penny,” said Geller, who served in the Florida legislature for 20 years and is a former president of the National Council of Insurance Legislators.

The insurance industry is lining up against the legislation.

“A federal (re)insurance program is not needed; it does not address the root causes of insurance premium increases in certain parts of the country and would only increase risk and resulting premiums by encouraging development in high-risk areas,” Covington said in the RAA statement. “We do believe the federal government has a significant role in promoting risk mitigation and directing funding and other resources to reduce property risk,” such as efforts undertaken by the Federal Emergency Management Agency on disaster resilience zones.

Triple I is also leery of a federal role in reinsurance.

“History has shown that direct government involvement in the underwriting and pricing of insurance products tend not to end well,” Friedlander said in the Triple I statement. As an example, he pointed to the National Flood Insurance Program, which carries significant debt and an operating deficit.

The reinsurance plan in the bill “would place a burden on Florida taxpayers via a special assessment of 1% to 3% of home insurance premiums for up to a decade to pay off Treasury notes,” Friedlander added. “Floridians already pay the highest average insurance premiums in the US and are not looking to pay more.”

Geller, who said he helped write the bill, is confident that support can be built for the measure because severe weather’s impact on insurance costs is a national problem.

“The issue is becoming more and more important not only in Florida but in many states across the country, particularly every coastal state,” Geller said.

The bill was introduced by Rep. Jared Moskowitz, D-Fla., last May. It has not received a hearing in the House Financial Services Committee and has not attracted any cosponsors. Moskowitz’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

Geller said Moskowitz, a former Florida state legislator and the state’s former emergency management director, can get the bill moving because he can work across the political aisle.

“One of the reasons Jared is such a good sponsor is he plays well with others,” Geller said. “He has a great deal of credibility.”

If the bill is not approved by Congress by the end of December, it would have to be reintroduced in the new Congress that takes office next year.