With geopolitical tensions on the rise, a troubling conflict in Gaza and Russian threats to the West, the Doomsday Clock is ticking perilously close to midnight. Insurers are seeing an uptick in political violence and terrorism (PVT) insurance policies – close to the surge seen following 9/11 and after the creation of the Terrorism Risk Insurance Act (TRIA) in 2002.

Chris Kirby (pictured), program president at Starwind, told Insurance Business that PVT insurance has undergone significant changes in response to global crises.

“Primarily, we write back the exclusions within an all-risk policy,” Kirby explained. “An all-risk policy will cover everything and then exclude a whole host of different risks. Since 9/11, terrorism has been one of those exclusions, driven by the reinsurance market. You have the retrocessional market at the top, which then releases capacity down through the reinsurance treaty market, which filters down to the direct insurance market. So we are driven by what reinsurers allow us to cover – or what they exclude from all-risk policies. We then develop products to write those perils.”

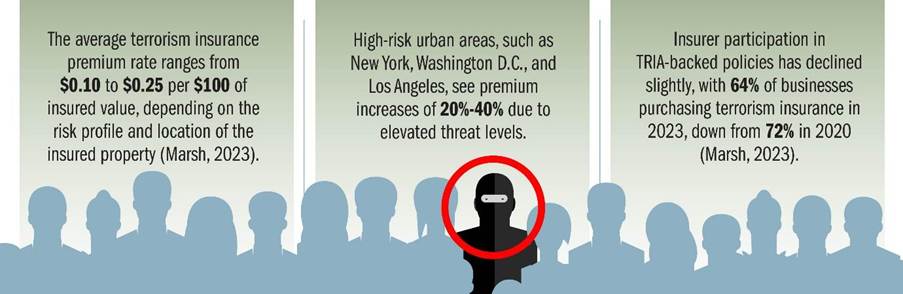

While some terrorism coverage existed before 9/11, it was limited. The UK developed Pool Re after IRA attacks in the 1980s, and a small UK terrorism private market formed to compete against it. Colombia, Sri Lanka, and other countries also had demand for terrorism coverage. The standalone terrorism market, however, only really took off after 9/11. According to research, the US standalone terrorism insurance market is estimated at $1.5 billion to $2 billion annually, with major insurers including AIG, Lloyd’s of London, and Chubb offering coverage.

“The Arab Spring was a major turning point – it was the first time the limitations of our policies were tested,” Kirby said. “Clients began demanding strikes, riots and civil commotion (SRCC) coverage alongside terrorism policies. The next evolution came with war on land coverage. Once we could start writing domestic war on land, we provided the third pillar of political violence coverage. Not all countries demand all three – some want two, some only need one. It depends on what the threat is, and what the all-risk market is excluding.”

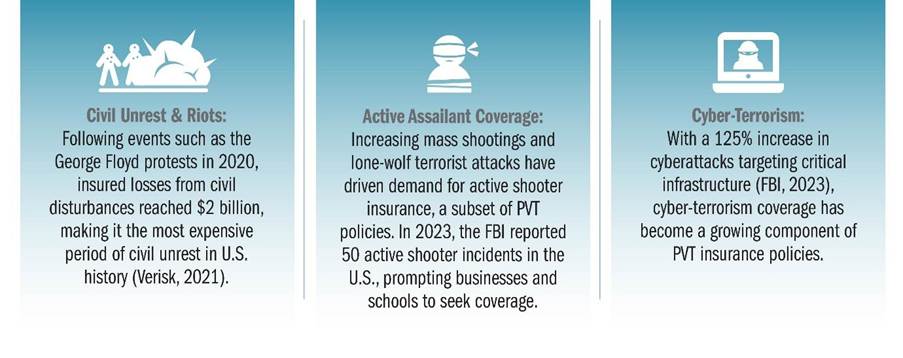

The last decade has seen an increase in civil unrest claims, with significant consequences for insurers. From 2019 to 2021, there were high-frequency, high-severity protests and riots, unlike anything the market had dealt with before.

The biggest claims stemmed from:

“These events happened one after another, and it was the first time we saw this level of severity and frequency in a short period,” Kirby said. “Before that, even with losses in Syria, Yemen, and the early days of the Ukraine conflict, we hadn’t seen that kind of claims volume. The knee-jerk response was that some property markets started excluding protests and riots. That’s since settled down, but it highlighted vulnerabilities in how insurers approached these risks.”

And while demand for standalone terrorism insurance has increased, many policyholders mistakenly believe TRIA covers all terrorism-related losses.

“People forget that TRIA is a reinsurance program—it doesn’t operate like Pool Re in the UK, which pays out claims directly,” Kirby said. “Now, people are realizing the restrictions of TRIA – it doesn’t cover domestic terrorism, for instance. We’re being asked for terrorism quotes more frequently, because property insurers are now questioning whether certain domestic incidents qualify under TRIA.”

Beyond terrorism, broader economic and social trends are driving PVT insurance demand. There has been a clear increase in social and economic tensions post-COVID, with Kirby adding that he’s now seeing the delayed effects of quantitative easing from the 2008 financial crisis, and now inflation is hitting certain economies hard. Another key area of concern is public sector unrest.

“Some governments are struggling with wage disparities and recessionary pressures,” Kirby said. “Heavily unionized public sector workers are feeling the impact, and that can lead to protests, which sometimes escalate into riots.”

In many cases, these protests turn violent quickly, even if they start peacefully.

“A very small percentage of participants can escalate a protest into a riot,” Kirby said. “Sometimes, these events are infiltrated by nefarious groups, and sometimes law enforcement actions inadvertently escalate tensions.”

And, as social unrest and political violence increase, insurers are adjusting their policies.

“Today, we’re seeing a polarization of political parties worldwide,” Kirby told IB. “There’s less middle ground – more people are taking extreme stances, and that heightens tensions. Right now, we’re hearing more about the right versus the left, and each side is accusing the other of extremism. This kind of political division feeds into social movements, which can escalate into violent events.”