Laws and structures compensating workers for injuries incurred on the job have been in place for 100 years in the United States, conjuring images of a time when risks to life and limb were an inevitable part of the working landscape.

In reality, though, as employment has moved away from manufacturing to an information- and service-based economy, and as workplace risks to employees have shifted from physical to mental, workers’ compensation has evolved in tandem with employment trends.

“Originally, workers’ compensation was fundamentally about traumatic injuries in the workplace,” says Mark Walls, chief marketing officer at Safety National and founder of Work Comp Analysis Group.

Walls, who has over two decades of experience in the workers’ comp field, says, “Over time, you saw that start to change as occupational diseases came into play. That was an add-in to workers’ compensation that recognized there were certain exposures in the workplace that could lead to diseases that could take years to manifest. More and more states now recognize repetitive trauma claims, which tend to occur gradually over time, and create wear and tear on the body.”

Economy, technology making workplaces safer

Over the course of this evolution, the workplace has become increasingly safe. Much of that is due to a steady reduction in physical risks as jobs have shifted to a service and information economy. And in jobs that still carry significant potential for accidents, technology is helping create safer workspaces.

“You’re starting to see things like wearable technology being used in construction,” says Walls. “Wearables can track someone’s location and body temperature and detect if there’s a fall. It’s a fantastic technology that allows you to literally monitor your workforce in real time.”

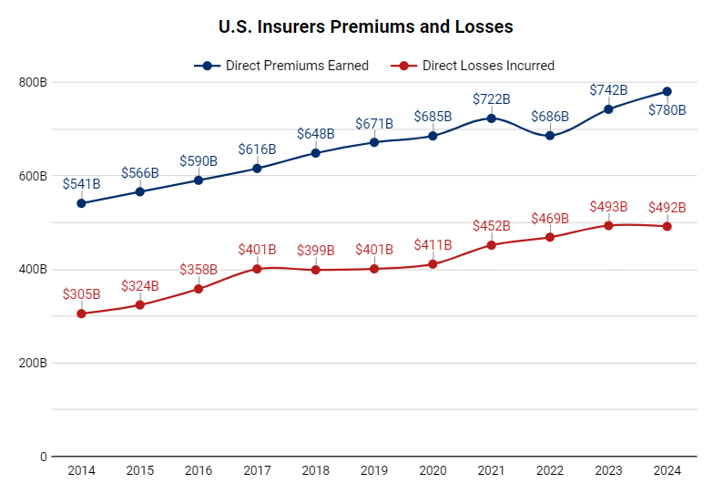

Walls emphasizes that these types of technologies are helping to push the accident frequency trend downward. For that reason, insurance premiums and losses for workers’ comp are moving in the opposite direction of overall insurance premiums and losses.

A Tale of Two Premiums

Despite safer workplaces, new comp cost drivers are a concern

The trend of declining losses and premiums for workers’ comp is occurring even though the average cost per claim is rising. Technology is again the driver, but this time, the technology underpinning incredible advances in medical care is driving costs upward.

“The cost of big claims has increased exponentially, at a much greater pace than inflation, and that’s in response to advancements in medical care,” says Walls. “The survival rate for traumatic injuries is up dramatically over the last 15 years. And then on the back end of that, for people who are more severely injured – as in the case of brain injury, spinal injury, severe burns, etc. – the medical science is such that it really has given those people a greater quality of life and a longer life expectancy.”

The result is workers with traumatic injuries are settling compensation claims that fund medical treatment and sometimes 24-hour care for decades. As Walls notes, “They’re a small piece of the overall system, but they are a big cost driver.”

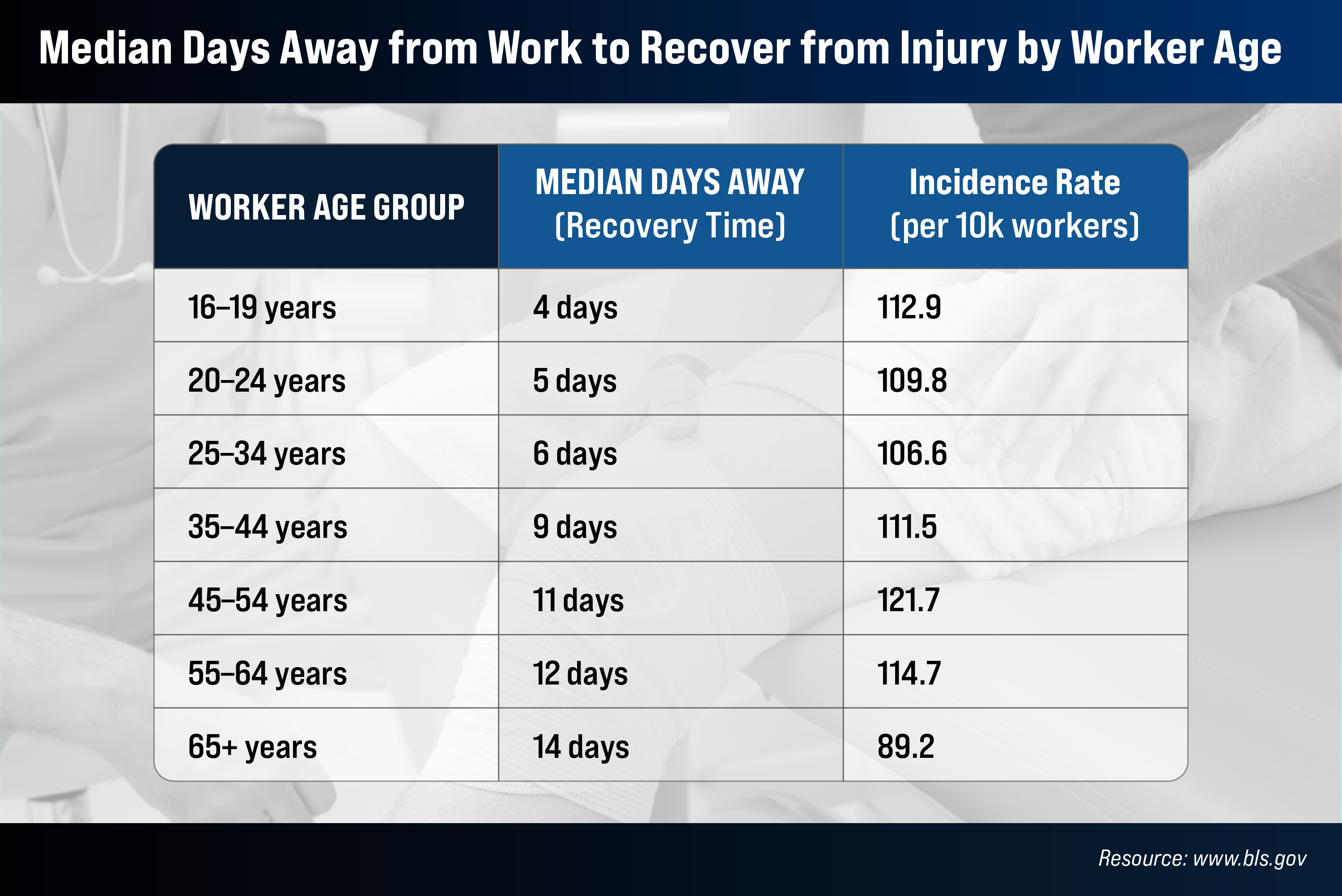

Additional cost drivers are tied to the changing demographics of the US workforce. Older workers – those over 65 years of age – were once a rarity in workplaces. Not anymore. Not only are there more workers over 65 years old, but the Bureau of Labor Statistics also projects a 96.5 percent growth in the workforce aged 75 and older between 2020 and 2030 (Employment projections: Civilian labor force, by age, sex, race, and ethnicity).

And while all that work experience typically results in safer workplace behaviors, when accidents do occur among older workers, recovery typically takes longer, driving compensation costs higher.

At the other end of the spectrum, younger workers are not only statistically more likely to suffer physical injuries but may also take longer to return to work.

“Early speculation suggests that the trend has to do with a generation more focused on their own well-being and achieving work-life balance,” Walls says. “Therefore, they really don’t want to go back to work until they feel 100 percent, as opposed to returning to a modified job.”

This is another area where workforce demographics have the potential to drive up costs.

Mental health is the next frontier, but the full impact is yet unclear

Insurers are keeping a close eye on these rising costs, especially as premiums decline. But workers’ comp professionals are also watching an emerging trend that may come to dominate the US workers’ comp system: the impact of work on employees’ mental health.

“The next evolution of workers’ compensation is around mental health,” Walls says. He believes this broad and largely undefined category could have a monumental impact on the workers’ compensation landscape.

“In response to school shootings in Florida and Connecticut, laws were passed to create presumptions – an acknowledged workplace risk – for the first responders on post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and I don’t think anybody would argue with that being a traumatic experience,” Walls says.

“But what about the teachers in those schools? What about my boss yelling at me in a workplace interaction? You can see that the potential is there. With a narrow interpretation, I don’t think that it’s hugely impactful. But with a broad interpretation, you could see how this could just fundamentally change workers’ compensation.”

For now, workplace-related mental health risks are a massive gray area for insurers, employers, and lawmakers, who will need to develop parameters around what constitutes a legitimate mental health claim. In doing so, two issues will have to be addressed.

The first is the intersection of mental health compensation claims with existing health benefits that employers offer. As Walls notes, it’s not a case of going from no support – as with physical injuries – to a workers’ comp claim based on mental trauma. Support such as counselling are covered under employee benefit programs at many companies.

“From a claims perspective, companies and insurers have a lot of figuring out to do,” Walls says. “I don't think we’re going to see this fundamental, impactful change right away. It’ll be gradual.”

The second, perhaps bigger, challenge involves separating mental health impacts that are work related from those that aren’t. This factor differentiates physical health from mental health-related compensation claims.

“For example, if your arm was amputated by a drill press, there’s no question that it’s work related, and you can see it. But mental health professionals are trained to treat you holistically. They’re not going to focus on the work trauma; they’re going to focus on you, the patient,” he says.

There’s an additional dilemma related to patient privacy. Many claimants may not wish to share patient records with an insurer, as mental health can carry a stigma that physical injury does not. And without documented evidence, insurance companies cannot pay out a claim.

Trauma due to workplace violence is a core mental health driver

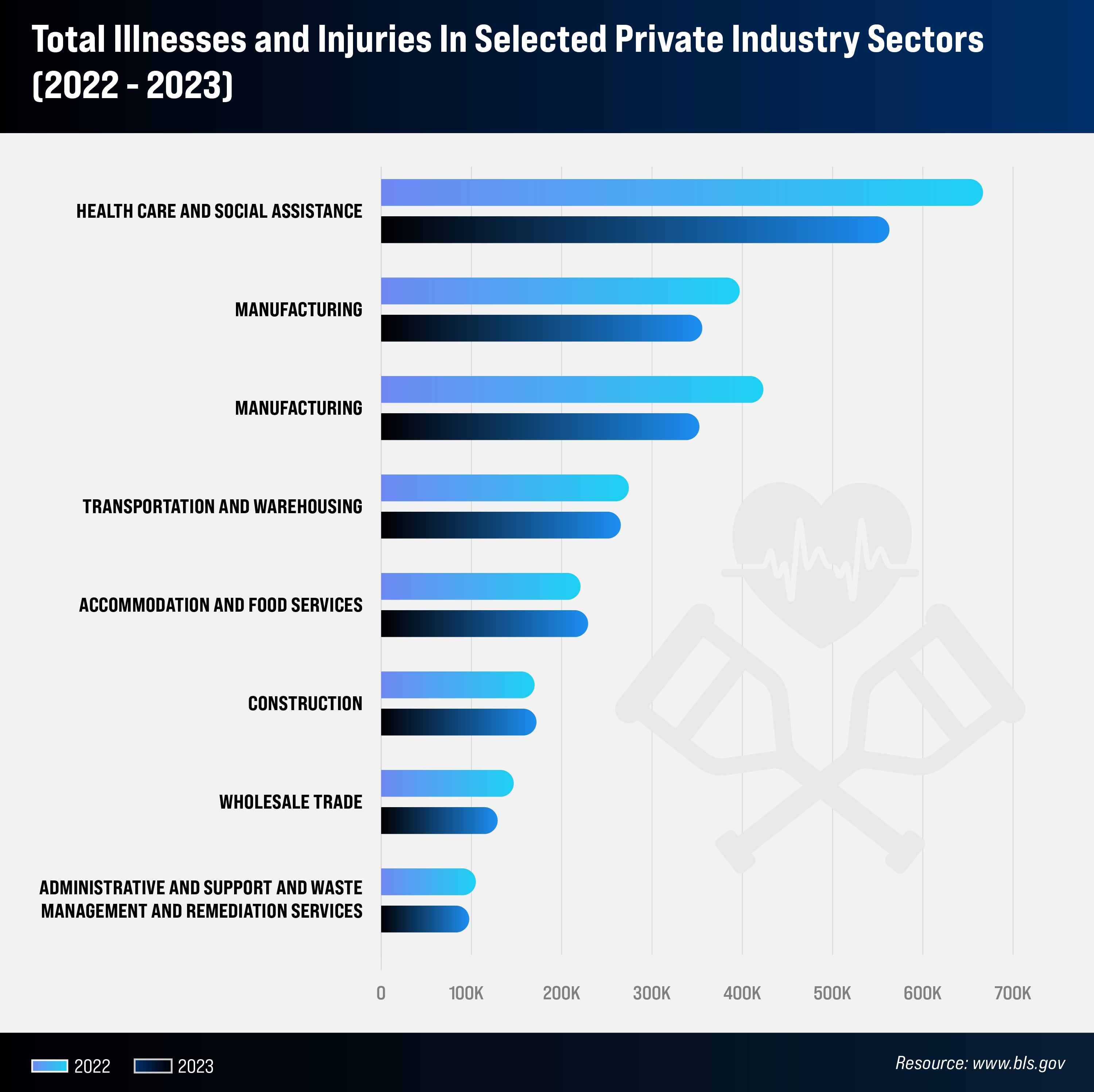

Mental health impacts in the workplace continue to escalate, and much of it is tied to workplace violence.

“Workplace violence is a scourge that we see and it’s heavier in some industries than others, but everybody gets a piece of it,” Walls says.

He notes a leading workers’ comp challenge in the health care field, among first responders, as well as for teachers and hospitality workers, is violence on the job. Physical assaults also result in bodily injuries, as well as mental trauma.

“Any profession where you’re interacting with people, you get people behaving badly. And so those two things – physical injury and mental trauma – tie together. Maybe you’re not the one that gets physically assaulted, but you’re standing there when it happens, and you’re traumatized by that. So, the two things go hand in hand,” he explains.

Outside of workplace violence, the connection between mental health and physical injury is still there. Unaddressed mental health issues, whatever their cause, often lead to workplace accidents. To address this, the State of New York has recognized the importance of mental health in the workplace and recently introduced legislation permitting compensation claims tied to job-related stress, extending a benefit previously restricted to first responders (2025 Workers’ Compensation Outlook: Key Trends and Challenges).

Companies remain committed to employee safety

This initial expansion of what constitutes mental trauma is both the tip of the iceberg and “a new frontier because there’s no data around what this is going to cost the system. Ultimately, what it’s going to come down to is judicial interpretation,” Walls says.

And while the impact of mental health claims on the future of workers’ comp in the US is unclear today, Walls is confident the system will make the adjustments necessary to ensure the health and safety of American workers.

“Overwhelmingly for most employers, their workforce is their most valuable commodity. And they care, they truly care. They want to keep their workforce safe, healthy, and happy,” he says.

The expanding legal landscape of mental health claims

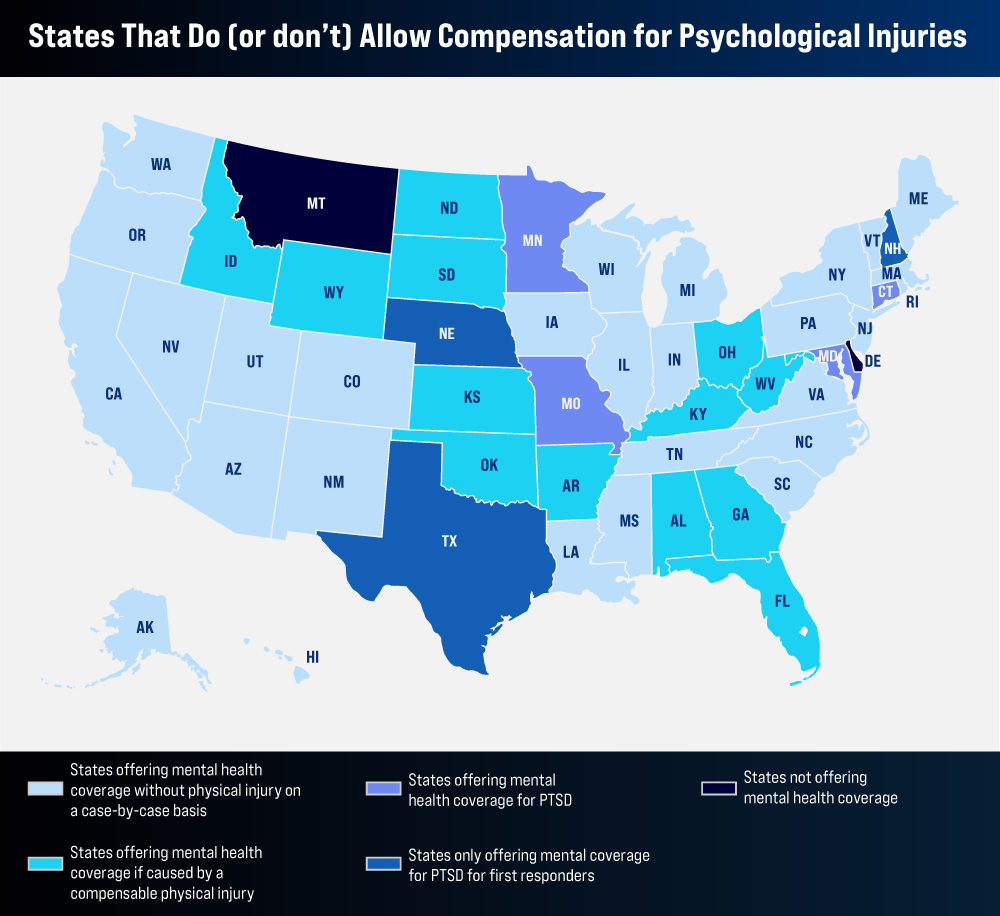

Historically, workers’ compensation frameworks required physical injury as the gateway for mental health-related claims. That gate is now opening. As of January 2024, 31 states, plus the District of Columbia, allow workers to file claims for mental health conditions arising from work-related factors, even without a physical injury. In every state except Delaware, mental health claims are recognized when linked to physical trauma or cumulative workplace stress. This represents a marked shift from a time when many jurisdictions excluded purely psychological conditions from coverage

First responders have mainly led the push for reform. In recent years, numerous states have passed legislation presuming that PTSD or related psychological injuries among police officers, firefighters, EMTs, and correctional officers are work-related. These changes acknowledge the acute trauma often experienced in these roles and ease the burden of proof for affected workers. States like Florida, Missouri, Washington, and Idaho have expanded or solidified such presumptions in recent years.

At the same time, the healthcare industry has emerged as another focal point for reform. Mental health strain among nurses and caregivers – exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic – has prompted some states to explicitly extend PTSD and trauma-related coverage to frontline medical professionals. This includes coverage for psychological harm stemming from patient aggression or persistent stress exposure in care settings.

More broadly, some states are testing the limits of compensability. New York and Connecticut have passed laws enabling claims for extraordinary workplace stress, expanding mental health protections beyond first responders to encompass general occupations. These policies reflect growing recognition of chronic occupational stress, burnout, and cumulative trauma as legitimate medical conditions.

Still, acceptance of such claims remains uneven. While anecdotes point to a gradual rise in filings, mental health injuries remain difficult to evaluate and adjudicate. Insurers face hurdles in establishing causality and navigating privacy concerns, and claimants may hesitate to disclose personal health histories. As more jurisdictions clarify legal thresholds and claim protocols, a fuller picture of mental health claim trends may emerge.

Legislatures lead the charge

The past five years have seen an unprecedented level of legislative activity surrounding work-related mental injuries. Between 2022 and 2023 alone, lawmakers introduced more than 140 bills focused on PTSD and psychological harm in the workplace. These measures range from expanding eligibility to creating formal diagnostic and claim evaluation standards.

In addition to broadening coverage, some laws address the stigma of mental illness by strengthening confidentiality protections and investing in peer counseling programs. Other states are exploring presumptive coverage rules for high-risk professions, making it easier for impacted workers to access benefits without an extended legal process.

Related article: Oklahoma bill expands PTSD coverage for first responders’ protection

As this patchwork of reforms takes shape, employers and insurers are adapting. Many have begun developing guidelines for evaluating mental health claims, revising claims handling protocols, and investing in preventive strategies – from employee assistance programs to trauma-informed training for supervisors. While a uniform national standard remains elusive, the trajectory is clear: mental health is no longer a fringe issue in workers’ comp.

The aging workforce: fewer claims, longer recoveries

While mental health is reshaping coverage, demographics are reshaping claim patterns. As more Americans work past traditional retirement age, new challenges are surfacing in the form of extended recovery times and elevated claim severity.

Contrary to conventional wisdom, older workers are not more prone to workplace injuries. In fact, data shows that injury frequency decreases with age. However, when older employees do get injured, they typically take longer to heal and may incur higher medical costs due to comorbid conditions.

For example, a worker aged 65 or older may take two weeks or more to return to work after an injury – roughly three times the recovery period of a teenaged worker. Falls are particularly problematic, as older workers are more likely to suffer fractures and other serious injuries from incidents that younger employees might walk away from. Nearly half of injury claims for senior workers stem from falls, underscoring the need for age-aware workplace design and prevention strategies.

Despite these challenges, the net cost impact of an aging workforce is not as dire as once feared. While claim severity rises with age, frequency declines, keeping average per-worker claim costs relatively stable. Moreover, many older workers are part-time or in lower-wage roles, which moderates wage-replacement benefits. As a result, the system has thus far absorbed these demographic shifts without major dislocation.

The growing threat of workplace violence

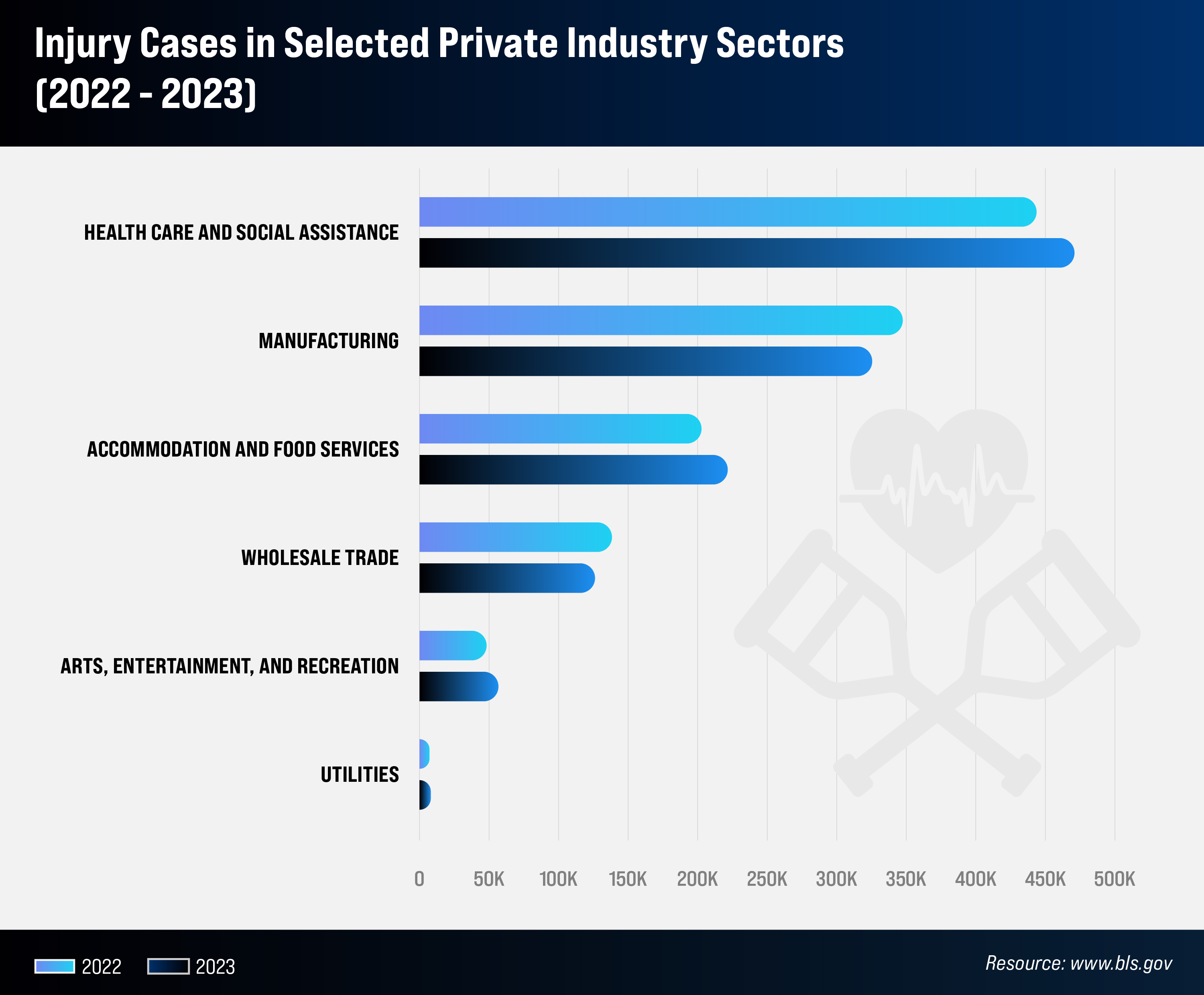

Another intensifying challenge to workers’ comp stability is workplace violence, particularly in service industries. From physical assaults to traumatic incidents, violence is driving both physical injury claims and a new wave of mental trauma cases.

Healthcare and social assistance workers face the brunt of this trend. Though they comprise about 10 percent of the US workforce, they account for nearly half of all nonfatal workplace violence injuries. Nurses, aides, and mental health workers routinely face aggression from patients or their families. This persistent exposure to violence not only leads to physical harm but contributes to rising PTSD and anxiety claims.

Outside of healthcare, educators, retail staff, and hospitality workers are increasingly exposed to similar risks, whether through direct attacks or through vicarious trauma from witnessing violence. Legislation and Occupational Safety and Health Administration guidance are emerging in response, including new mandates for violence prevention plans in hospitals and schools. Employers are investing in de-escalation training, physical security, and employee assistance resources to reduce the toll.

From a compensation standpoint, violence-related claims are among the costliest. They often involve extended lost time, legal complexity, and significant mental health follow-up. Insurers and regulators alike are watching this trend closely as it intersects with broader mental wellness concerns.

Fragile balance between medical costs and premiums

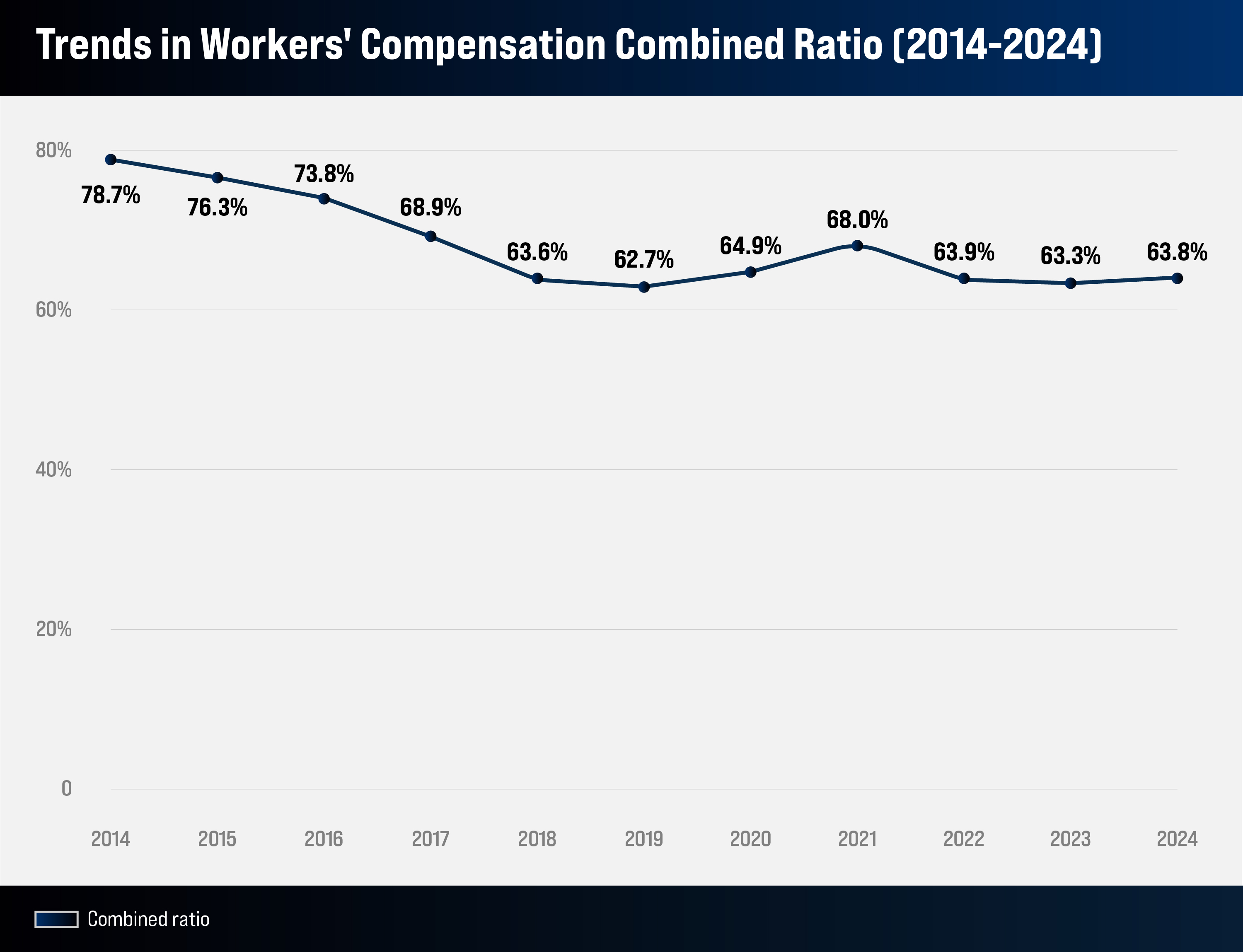

Beneath the shifting landscape of claims lies an economic story: despite rising medical costs, employers are paying less for workers’ comp insurance than they did five years ago. While individual claims – especially severe injuries – are becoming costlier due to medical advances, the total number of claims has dropped so significantly that overall system costs and employer premiums have continued to decline.

While general healthcare inflation has surged, workers’ comp medical cost growth has remained surprisingly tame – just one to two percent annually in recent years. This is partly due to state fee schedules, treatment guidelines, and falling pharmaceutical costs following the opioid crackdown. At the same time, many states have cut workers’ comp rates as losses dropped, with several jurisdictions seeing multi-year declines in manual rate filings.

The result is that employers today enjoy some of the lowest premium costs in decades, even as benefits remain robust. This trend has boosted insurer profitability, with the industry reporting combined ratios below 90 percent for 10 consecutive years – a strong underwriting performance by any standard.

Still, this equilibrium may not hold forever. Actuaries warn that new pressures – like wage inflation (raising indemnity costs), litigation, and expensive new medical treatments – could eventually reverse course. For now, however, the system remains financially resilient, balancing employer affordability with insurer solvency.