New Zealand experienced its 10th-warmest year on record in 2024, according to the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA).

Data from NIWA’s seven-station series, which has tracked national temperatures since 1909, recorded an average temperature of 13.25°C to 0.51°C above the 1991-2020 baseline.

The 2024 findings align with an ongoing warming trend both in New Zealand and globally, driven by rising greenhouse gas emissions. Atmospheric carbon dioxide levels measured at NIWA’s Baring Head monitoring station exceeded 420 parts per million (ppm) during the year, a notable increase linked to human activities.

Above-average annual temperatures were observed in several regions, including Northland, Waikato, Hawke’s Bay, and parts of Otago. These areas experienced increases ranging between 0.5°C and 1.2°C above historical norms. However, March and May deviated from this trend, recording temperatures 1.3°C and 1.0°C below their respective monthly averages, making them among the cooler months in recent years.

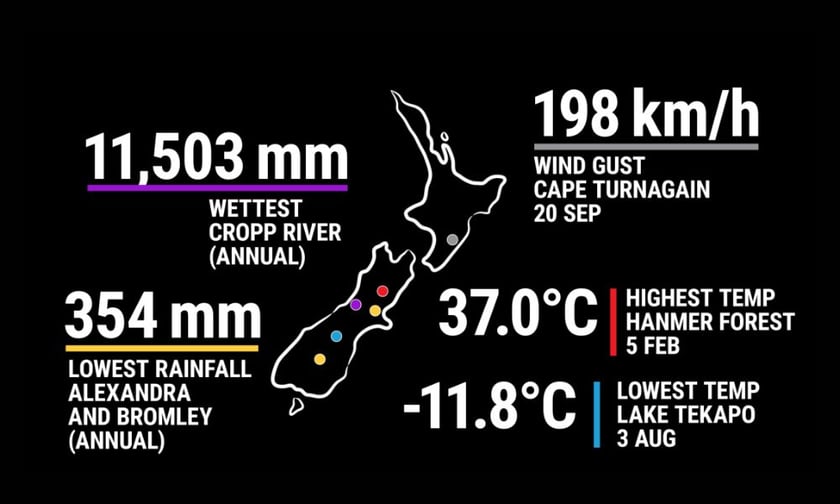

Rainfall patterns in 2024 varied significantly. Regions such as Northland, Bay of Plenty, and eastern Canterbury reported below-normal rainfall, with some locations experiencing their driest year on record. Conversely, parts of Southland and Otago received significantly more rain than average, contributing to saturated conditions and flooding in some areas.

Soil moisture fluctuated over the year, with below-average levels in the early months, particularly in regions such as Wairarapa and Taranaki, which faced drought conditions.

By winter, moisture levels had largely recovered, though drier-than-normal conditions returned in parts of the North Island by year-end.

Meanwhile, Marlborough retained its reputation for sunny conditions, with Blenheim recording the country’s highest annual sunshine total at 2,769 hours.

The year’s climate was shaped by shifting weather patterns, including the effects of a weakening El Niño early in the year. These patterns brought westerly and south-westerly winds that contributed to drier conditions in sheltered northern and eastern areas.

Several extreme weather events occurred, including flooding in Westland, Wairoa, and Dunedin, prompting local emergency declarations.

Sea surface temperatures (SSTs) also influenced the climate. After cooler-than-average SSTs during autumn, temperatures in surrounding waters returned to above-normal levels later in the year, peaking in late January and early February.

Experts highlighted the broader implications of New Zealand’s warming climate.

Dr Nick Cradock-Henry, a principal scientist at GNS Science, noted the uneven impacts of warming and shifting rainfall patterns, emphasising the importance of long-term planning for land and water management.

“Enhancing resilience and accelerating adaptation action to safeguard lives and livelihoods will be an essential part of New Zealand’s response planning, going forward, regardless of how 2025 unfolds,” he said.

Dr James Renwick, a physical geography professor at Victoria University of Wellington, pointed to the critical role of consistent climate monitoring in helping New Zealand respond to ongoing changes. He emphasised the need to adapt infrastructure and systems to prepare for continued variability in climate conditions.

“The NIWA annual climate summary, the underlying observational network and team of scientists analysing the data, are a critical part of the country’s science infrastructure. Ongoing measurement of what’s happening on the ground is crucial to understanding how our climate is changing and how we adapt,” he said.